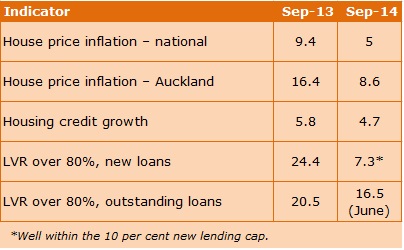

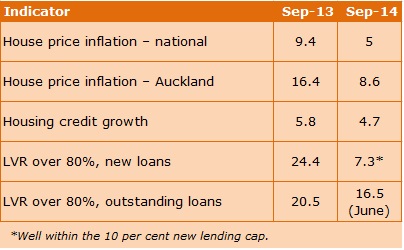

The macro-prudential tools developed by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) to contain a bubble in the housing market appear to have succeeded beyond expectation in the first two years, although the effect has now tapered off.

Since 1 October 2013, the RBNZ has required banks to ensure that 90 per cent of any new home lending must have a loan to value ratio (LVR) of at least 80 per cent – meaning that home buyers need to front up with 20 per cent of the purchase price.

The RBNZ’s modelling indicated that the intervention would reduce house sales by around 5 per cent, house price inflation by 1-4 percentage points and growth in new mortgage lending by 1-3 percentage points; and that these effects would allow the 90 day bill rate to stay 30 basis points lower than would otherwise be necessary.

All of these projections were met, according to a set of “key effectiveness indicators” in the RBNZ’s latest half-yearly Financial Stability Report (published in November).

Over this period, interest rates remained low by historic standards and the RBNZ lifted the Official Cash Rate (OCR) just once, in March 2014 by one percentage point. Yet the volume of house sales was down 12 per cent since the LVR policy’s introduction.

The limits were always intended to be temporary and there was a general expectation, including on the part of the Finance Minister, that the RBNZ would lift them when it reported in November.

However it has elected to continue them for the meantime because strong immigration flows are creating price pressures, particularly in Auckland, and because prices are still “elevated” compared to both income and rents. (It is also worth noting, although the RBNZ didn’t mention it, that although growth in household lending has slowed, it is still outpacing GDP growth.)

The RBNZ accepts that many factors influence housing market conditions but considers that the LVR policy has had “a substantial impact on housing demand”.

A number of jurisdictions, including Israel and Hong Kong, have applied LVR restrictions but New Zealand was the first – to the RBNZ’s knowledge – to apply a “speed limit” on any new lending over the specified LVR maximum, rather than an outright ban.

Ireland has this week introduced a variant on the RBNZ approach, requiring that no more than 20 per cent of new mortgages should have a Loan-to-Income ratio greater than 3.5 and that no more than 15 per cent should have Loan-to-Value ratios greater than 80 per cent.

All of which may be relevant in the Australian context given the RBA Governor’s musings in November about double digit credit growth in the residential property investment sector and whether this should prompt “a reasonable observer” to ask whether “some suitably calibrated and focused action to help ensure sound (lending) standards, and that might lean into the price dynamic, may be appropriate”.

Significantly, in relation to the RBA Governor’s dilemma, one of the distortions created by the LVR restrictions is that they have hit first home buyers hardest. The proportion of sales going to this group has dropped to 17 per cent from a peak of 21 per cent in September 2013 while that going to investors has risen from 37 per cent to 40 per cent.

To quell this activity, the RBNZ is exploring new mechanisms to push the banks to charge commercial property interest rates (typically 2.5 to 3.5 percentage points higher than the standard mortgage rate) on these loans by requiring them to hold larger capital reserves to cover against any potential losses through default.

The design of the regulations is reportedly causing some headaches, in particular how to target the regime. The RBNZ initially considered targeting investors with five or more investment properties but is now exploring an income based model which would look at how much of an investor’s total income was derived from their residential property portfolio.

Otherwise the framework has proven remarkably robust. The only other tweak, introduced in December 2013, was to exempt new builds after feedback from the building industry that the LVR limits were impeding new house construction – an effect which, if allowed to continue, would constrain housing supply and eventually push up prices on existing stock.

The RBNZ reports that the banks have complied with the “spirit” of the policy rather than seeking to game it. This does not surprise us. In fact we predicted that the banks would allow themselves headroom to ensure that they didn’t breach the 10 per cent cap as non-compliance could cost them their registration.

Ross Pennington

Ross Pennington is a partner at Chapman Tripp specialising in finance. He is named as a leading lawyer IFLR1000 2014 and Chambers Asia Pacific 2014 and is listed in the International Who’s Who of Capital Markets Lawyers.