K3 Legal's thought on Therapeutic Justice, Singapore’s fresh approach to dealing with divorce

This article was provided by K3 Legal

K3 Legal’s family law team visited Singapore in mid-2023 and had some thought-provoking conversations with our Singapore colleagues on Singapore’s fresh approach to dealing with divorce – Therapeutic Justice.

In the Family Justice Courts Workplan 2020, Justice Debbie Ong set out this new pathway in the Singapore family courts. The two main focuses of Therapeutic Justice are:

This view is based on the consideration that:

“divorce should be no worse than a re-organisation of family members’ living arrangements and the divorced spouses should still be able to continue to discharge their parental responsibilities with some degree of co-operation”.

Therapeutic Justice is explained as a way of looking at the laws and legal procedures through a “lens of care” and encourages family lawyers to help parties problem-solve, make rational decisions and take sensible steps.

Justice Debbie Ong further provides a list of things NOT to do, which will be incorporated into the family justice system and things the court will keep an eye out for:

Parties are reminded to not use court proceedings to vent frustrations, rather to use therapeutic services to support them in respect of emotional consequences.

We asked some respectable Singapore family law practitioners to share their thoughts and views on Therapeutic Justice in general, and also how that has shaped their practice since its introduction:

Ivan Cheong and Shaun Ho at WithersWorldWide:

Since the Court introduced and pushed for Therapeutic Justice as a guiding principle in divorce proceedings, ancillary matters proceedings, and other proceedings involving families, we have seen a gradual change in the way in which lawyers and parties have conducted such matters. Mediation takes place in a substantial majority of our cases now, even in cases where mediation is not mandatory (i.e. cases in which there are no children, or in which all the children have reached the age of majority). It has become easier to pick up the phone to just speak to opposing counsel about the matter, with both sides' counsel appreciating that guiding the parties to an amicable resolution would generally be in their interests, even if this means having to compromise on the substantive outcome. Inflammatory correspondence has also become less commonplace, and 'litigation by attrition' is all but absent in divorce proceedings these days.

The Court's own practice has also encouraged such constructive conduct in proceedings involving families. The Court has become more ready to intervene in cases to minimise animosity. The Court has also shown that it is more prepared, these days, to listen to the advice of social science experts. It does this by identifying cases with a high risk of being high-conflict through the introduction of triaging. Parties can in such high-risk cases be directed to seek the appropriate assistance from specialists, and such specialists are also encouraged to give their independent assessment about the parties, their conflict, and the children, to the Court. The Court of Appeal has even given specific guidance in a very recent 2024 case about how Judges can and should speak with children whose views are sought about the ongoing proceedings.

We think that the Court's push for Therapeutic Justice has been beneficial to the family law landscape in general – we are supportive of the Court's push and we think that the more lawyers practice in this way, the better outcomes generally are for the parties.

Amelia Ang at Lee & Lee:

While TJ is certainly an ideal, how do practitioners incorporate that in our first and foremost duty as our client’s advocate to advance their interest? Most clients still believe that any outcome would yield a “winner” and “loser” depending on which party gets what they want, and prefer that their lawyer fights “strongly” for their interests. This is especially so if we choose to adopt more “TJ” practices than the other lawyer who may still be aggressive (insisting on strict rights). Very often, this gives our client the feeling/sense that the other aggressive lawyer is protecting or advancing his clients’ rights more vigorously and effectively, as compared to what our proposed conciliatory approach, may be doing for him/her.

In short, a real challenge for family lawyers is to practice TJ in a way which upholds its ideals but yet can still inspire confidence from and “buy in” from their clients, bearing in mind that a TJ approach, being a solution driven approach, will need the clients to compromise and be more conciliatory that what they expect or are used to (as compared to other areas of law/litigation).

As such, it is not just lawyers who must learn now to incorporate TJ in their practice, it is imperative that the clients, the court users, accept and embrace the necessity and benefit of TJ as the way to resolve their family disputes.

Also, there may be a need for more specific benchmarks or metrics to assess what is or is not TJ-like practices? Otherwise, there may be differing standards among different practitioners or even judges, depending on each practitioner/judge’s personality, temperament and “appetite” to compromise! There have been instances when lawyers believed they were just advocating passionately (during a hearing or in their written submissions) for their client’s case, but only to be chided by judges that they were too aggressive and “un-TJ like”! What does TJ practices therefore mean, for the passionate advocate…

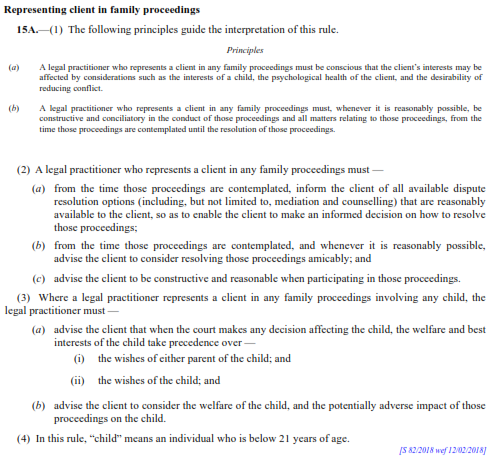

Being a family practitioner in Singapore can feel like you have a heavier and more onerous ethical duty than your peers in other disciplines. On top of the usual duties/obligations as a legal practitioner (to act in best interest etc) , family law practitioners are also statutorily required to “be constructive and conciliatory in the conduct of those proceedings”, “ advise the client to consider the welfare of the child” etc as set out at section 15A of the Legal Profession (Professional Conduct) Rules 2015.

Thoughts by K3’s family law team:

Rebecca Ong: New Zealand has elements of this approach when dealing with family law. This approach is reflected in section 9A of the Family Court Act 1980 whereby lawyers have a duty to promote conciliation in any proceeding in the Family Court. The section, however, does not go into detail on the “must dos” or “do nots”.

Mechanisms such as Family Dispute Resolution services exist as a sort of therapeutic justice where an independent mediator helps parents going through a separation discuss issues in hopes of reaching an agreement. Parents are barred from applying to the Family Court, unless they have already tried to resolve their disputes through the Family Dispute Resolution process. There are exceptions to this, such as when there is family violence involved. Another common resolution process in family disputes are round table meetings. It is a sit-down meeting where parties will attend together with their respective lawyers, and the lawyer for child. At these meetings, parties will attempt to resolve parenting and care arrangements, and reach a consent position with the aim of discontinuing court proceedings. While these are processes available to parties going through separation in New Zealand, it is not something that is enforced or endorsed by the courts such as the Therapeutic Justice approach is in Singapore.

Toni Brown: It is important to note that a lawyer’s responsibility is to present evidence in court that best serves the finder of fact to make decisions. It is not our role to outline all grievances or opinions of our clients. Sometimes, parties can be unhappy about not “being heard” on everything they feel is important to them, but if it does not assist the court in making a decision, it should not be before the court. For this reason, counselling is recommended, and is a process that sits separately (and hopefully before) any court process such that communication about grievances and issues can be ironed out before the legal process takes its own track.

Harriet Krebs: This Singaporean approach has merit. It is valuable to be able to reach a collective position, rather than a forced one as it creates longevity and sets the parties up with tools to enable ongoing conciliary consultation. Therapeutic Justice has had its place in New Zealand’s Criminal Justice System for some time. For example, those defendants whose offending is primarily due to their homelessness status, have the ability to attend the New Beginnings Court. This court enables defendants to access wrap-around support from ancillary organisations assisting with social and health issues. The process is long but has had success in cementing change for those who wish to participate. If Therapeutic Justice is to work in the family law sphere, there needs to be a real drive from the parties to partake in such a process. Without the intention, there will be no action. With family violence rife throughout New Zealand, it may be difficult to get the buy-in required to substantiate the alternative form of justice.

To conclude, Therapeutic Justice certainly is an interesting concept. It may be a suited approach when parties separated amicably, but it is difficult to see how this will play out when parties are embroiled in a long history of violence for example. Some elements are helpful reminders to family lawyers in general, such as to not send inflammatory letters, dig up evidence showing the worst of the other party for use in affidavits, or just to adopt an adversarial approach from the outset. Undoubtedly, family lawyers should approach cases differently to civil litigators or commercial lawyers. Family lawyers deal with an added layer of emotions when a relationship breaks down, and even more so when there are children involved. It will be interesting to see how Singapore family law practitioners, mediators, and the public themselves adapt to this approach and whether more countries should look to Singapore’s fresh take on dispute resolution in family law.

The Family Justice Courts Workplan 2020 is accessible here.