James & Wells' Ben Cain breaks down the most successful of these grounds

This article was provided by James & Wells

In last month’s article, Winners and losers: Reviewing trade mark opposition and invalidity grounds in New Zealand, I provided an overview of why it’s important to plead trade mark oppositions and invalidity applications based on the appropriate grounds. This week, I delve into the most popular grounds pleaded - and the apparent reasons for their success or failure.

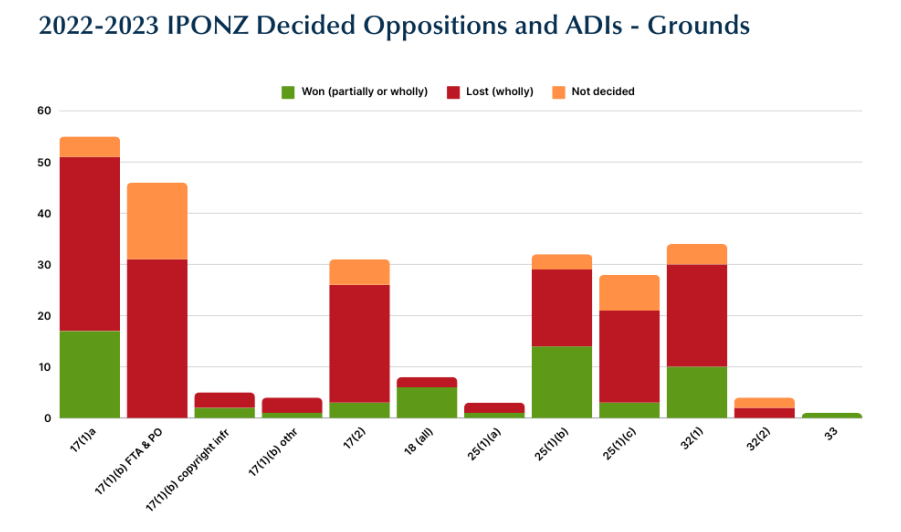

In 2022-2023, the most popular grounds pleaded were (in descending order):

As can be seen in the above chart, the top five most successful grounds of those pleaded on 10 occasions or more were (in descending order): s25(1)(b), s17(1)(a), s32(1), s25(1)(c), and s17(2).

As can be seen in the above chart, the top five most successful grounds of those pleaded on 10 occasions or more were (in descending order): s25(1)(b), s17(1)(a), s32(1), s25(1)(c), and s17(2).

Noticeably absent from the top five successful grounds is s17(1)(b) based on passing off and/or breach of the Fair Trading Act. More on this shortly…

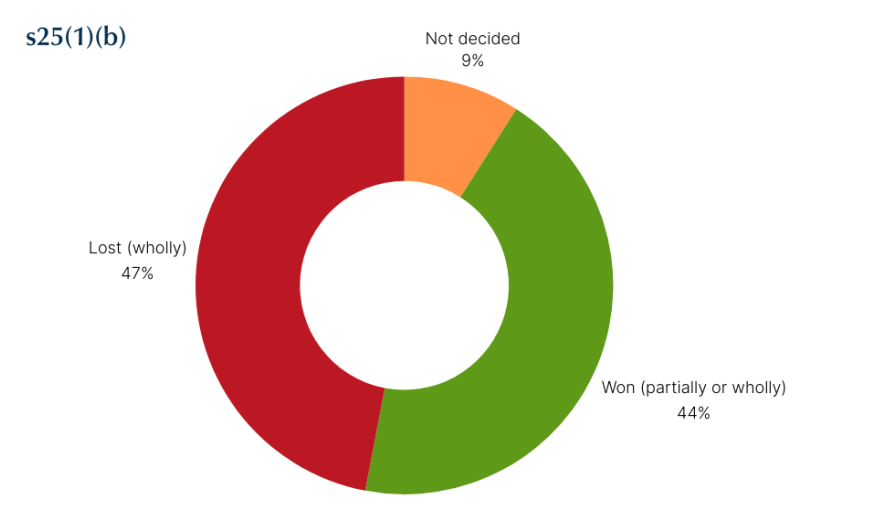

At a success rate of 44%, the position of s25(1)(b) at the top of the NZ list of successful grounds – which matches s44’s position at the top of the list in IP Australia oppositions4 – clearly demonstrates the value of having a registered right to rely on, especially in circumstances when an opponent/applicant is unwilling or unable to financially commit to pursuing a full opposition or invalidity with evidence and filing submissions or attending a hearing.

As to why s25(1)(b) was not successful, 53% of failures were due to the subject marks not being similar; 40% were attributable to either a lack of similarity between goods/services or, despite there being some degree of similarity between the subject marks, a lack of likelihood of deception or confusion; and 7% (representing only 1 decision) were attributable to pleading UK not NZ registered trade marks.

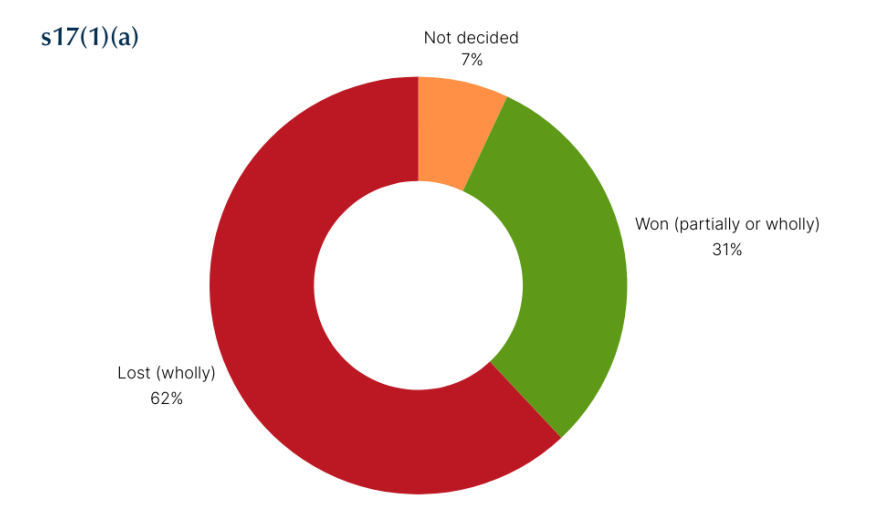

Given its position as the ‘go to’ ground of opposition and invalidity, s17(1)(a)’s success rate of 31% was (to me) surprisingly low. That said, its success rate was considerably higher than its s60 counterpart in Australia at a very poor 6%.

Given its position as the ‘go to’ ground of opposition and invalidity, s17(1)(a)’s success rate of 31% was (to me) surprisingly low. That said, its success rate was considerably higher than its s60 counterpart in Australia at a very poor 6%.

As to why s17(1)(a) was not successful, a whopping 62% of failures were due to insufficient evidence of reputation being filed by the opponent or applicant. Given the threshold to establish reputation is low, that is a remarkable statistic and potentially indicates opponents/applicants should think twice before pleading the ground, or amend their opposition/application to withdraw the ground either before or at the pre-hearing stage of proceedings. 12% of failures were due to inadmissible evidence (principally evidence not filed in the correct form), 9% of failures were due to the subject marks being dissimilar, and 18% of failures were due to a lack of likelihood of deception or confusion on account of dissimilar goods or services or the relevant surrounding circumstances of trade.

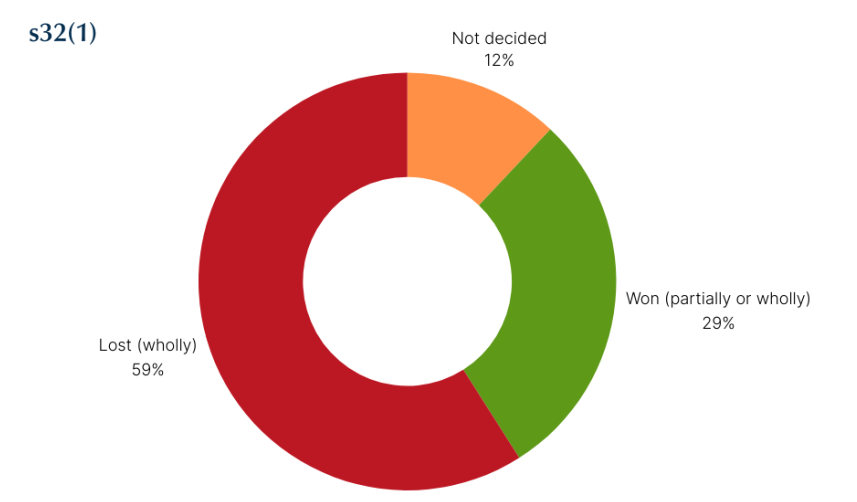

Oppositions and invalidities pleading s32(1) enjoyed a success rate of 29%, only marginally behind s17(1)(a).

Failure (or success) under s32(1) came down to one of five factors: the subject marks not being the same or substantially identical (30%), the evidence filed was inadmissible (20%), the scope of the opponent’s/applicant’s use was dissimilar to the goods or services in question (20%), insufficient evidence of prior use (25%), or the subject trade mark being distinctive and therefore capable of being owned (5%).

What the first four of these factors tend to show is that if a party is going to plead s32(1), then it needs to do so with establishing the legal tests very much in mind. In other words, it is not a ‘disposable’ ground as section 17(1)(b) passing off and/or breach of the Fair Trading Act might be.

In the last part of this article series, Cain examines the last three grounds that are popularly pleaded and draws conclusions from the analysis.