What are the legal responsibilities for directors of climate reporting entities under the FMCA?

This article was provided MinterEllisonRuddWatts

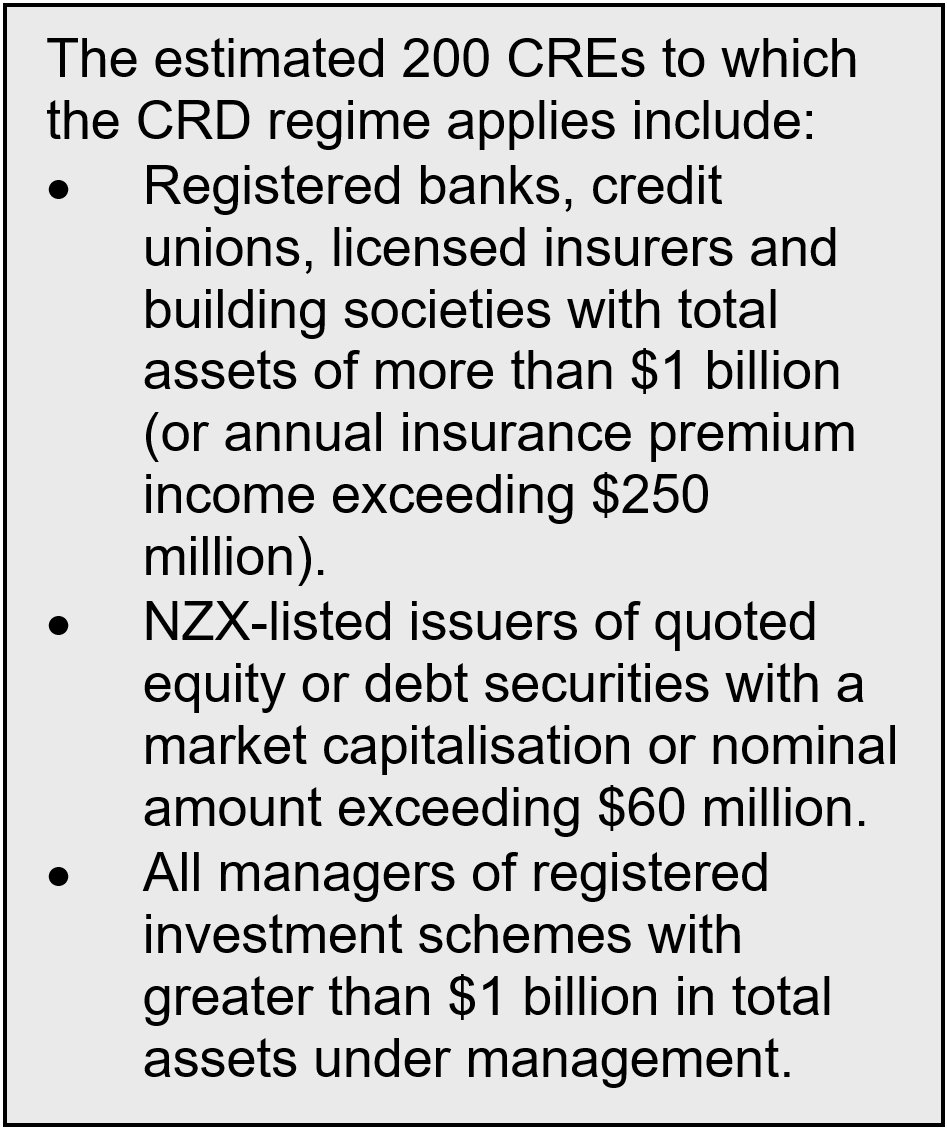

Directors of climate reporting entities (CREs) are currently grappling with the new climate-related disclosures (CRD) regime in the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013 (FMCA).

CREs must comply with Part 7A of the FMCA. This will require CREs to lodge, on the Disclose Register, statements that comply with the External Reporting Board’s climate standards (NZ CS).

Directors will be required to sign off on NZ CS-compliant climate statements. There are significant penalties for defective disclosure. That raises the question as to the level of enquiry directors should personally engage in to ensure the accuracy of the contents.

The legal responsibilities broadly parallel those for financial reporting under the FMCA. Climate statements and financial statements are intended to be released in tandem with the two reporting periods being the same, but directors should consider whether the same due diligence approach makes sense for both reporting regimes. The NZ CS requirements, like scenario analysis, are a particular pressure point for directors given their hypothetical and forward-looking nature.

This is where the FMCA defence in section 501(2) against civil liability for climate reporting contraventions comes in, which directors can rely on if they can prove they took “all reasonable steps” to ensure compliance.

Prain v Financial Markets Authority [2016] NZCA 298 is the most recent case to consider the “all reasonable steps” defence (in the context of the Financial Reporting Act 199 (FRA)). The Court of Appeal decided the directors of an entity that had contravened the FRA were reasonable to rely and act on their accountant’s advice. The Court noted that a second opinion may be necessary in circumstances where the directors have (or should have) doubts about the accuracy of the first opinion, but that was not the case in Prain.

Key takeaways

Although due diligence processes must be entity-specific, generally the approach should involve:

Due diligence processes should be documented in a written plan. When creating and monitoring these plans, directors should consider:

Good record keeping for due diligence will be critical. The FMA’s draft CRD record keeping guidance says:

“Without proper supporting documentation, it can be unclear whether an entity and its directors have sufficiently considered, understood, and reviewed their disclosures, and whether these are based on reasonable and well-considered inputs and assumptions”.

Efficient record keeping may look like an easily accessible, central digital platform to store all evidence related to the climate statement and its due diligence process.